היו מאות אלפי צופים!!

חלקם צפו כמה פעימים בסרט

רצינו להודות מקרב לב לכל אחד מכם

היו מאות אלפי צופים!!

חלקם צפו כמה פעימים בסרט

רצינו להודות מקרב לב לכל אחד מכם

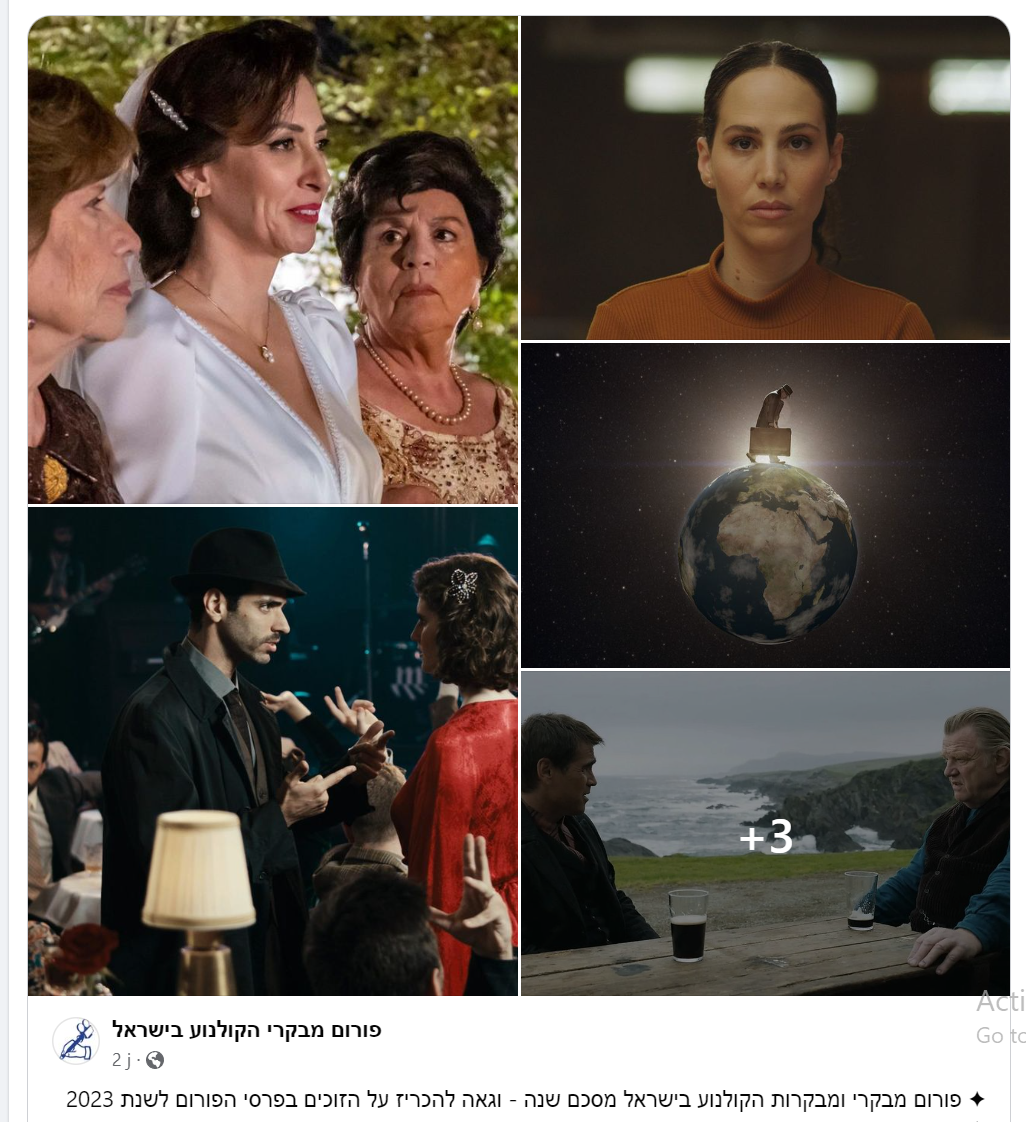

Excellent news! And very flattering! Our movie “The Shoshani Riddle” won Israeli Critics Association Award for Best Documentary in 2023. Thank you!

בשורות טובות! הסרט שלנו “חידת שושני” זכה בפרס הסרט התיעודי הטוב בשנת 2023

על ידי פורום מבקרי ומבקרות הקולנוע בישראל

כבוד לנו, תודה

https://www.mako.co.il/culture-articles/Article-38ed604716fbc81026.htm

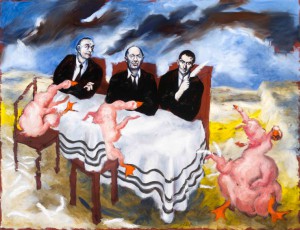

In this painting of the famous French painter Gerard Garouste “Three Masters and the fat gooses”, one can see Mister Shoshani sitting in the middle, between Kafka and Borges.

“Les trois maîtres et les oies grasses”, tableau du célèbre peintre contemporain Gérard Garouste.

On peut y voir Monsieur Chouchani assis au milieu entre Kafka et Borges.

Emmanuel Levinas est mort il y a vingt ans, le 25 décembre 1995. On connait son admiration sans limite pour son maître Monsieur Chouchani, “maître prestigieux – et impitoyable” selon ses propres mots. Il répétait à qui voulait bien l’entendre qu’il “n’avait rencontré dans sa vie que deux véritables génies, Heidegger et Chouchani”. Levinas fait également allusion à Chouchani à plusieurs reprises dans ses livres, par exemple dans “Difficile liberté” et dans ses “lectures talmudiques”. Nous vous présentons ici l’extrait d’un de ses livres, “Noms propres”. Jusque-là, on n’avait pas l’habitude de penser que ce texte pouvait faire allusion à Monsieur Chouchani. Mais un professeur de philosophie de l’université de Bar-Ilan, Dr. Hanoch Ben-Pazi, l’affirme : le dernier chapitre du livre parlerait sans le nommer du mystérieux génie. “Noms propres” est un recueil de portraits que Levinas dresse d’écrivains ou de penseurs aussi différents que Derrida, Agnon, Kierkegaard, Proust, ou Martin Buber. Mais le dernier chapitre du livre est intitulé “Sans Nom”. Il y est question de l’effondrement moral de l’humanité pendant la deuxième guerre mondiale et des enseignements à en tirer. Et il est aussi question dans ce chapitre de la condition si particulière du peuple juif. Il est vrai qu’on n’imagine pas Levinas penser au fait juif ni à la morale juive sans garder en arrière-pensée son “maître prestigieux” – un petit homme étrange, sans nom, qui l’a ébloui par ses océans de connaissances, ses capacités dialectiques hors du commun et ses fulgurances de génie. Alors voici un extrait de ce texte en question, peut-on le déchiffrer et y trouver un hommage à Monsieur Chouchani ? aux lecteurs de juger.

Emmanuel Levinas est mort il y a vingt ans, le 25 décembre 1995. On connait son admiration sans limite pour son maître Monsieur Chouchani, “maître prestigieux – et impitoyable” selon ses propres mots. Il répétait à qui voulait bien l’entendre qu’il “n’avait rencontré dans sa vie que deux véritables génies, Heidegger et Chouchani”. Levinas fait également allusion à Chouchani à plusieurs reprises dans ses livres, par exemple dans “Difficile liberté” et dans ses “lectures talmudiques”. Nous vous présentons ici l’extrait d’un de ses livres, “Noms propres”. Jusque-là, on n’avait pas l’habitude de penser que ce texte pouvait faire allusion à Monsieur Chouchani. Mais un professeur de philosophie de l’université de Bar-Ilan, Dr. Hanoch Ben-Pazi, l’affirme : le dernier chapitre du livre parlerait sans le nommer du mystérieux génie. “Noms propres” est un recueil de portraits que Levinas dresse d’écrivains ou de penseurs aussi différents que Derrida, Agnon, Kierkegaard, Proust, ou Martin Buber. Mais le dernier chapitre du livre est intitulé “Sans Nom”. Il y est question de l’effondrement moral de l’humanité pendant la deuxième guerre mondiale et des enseignements à en tirer. Et il est aussi question dans ce chapitre de la condition si particulière du peuple juif. Il est vrai qu’on n’imagine pas Levinas penser au fait juif ni à la morale juive sans garder en arrière-pensée son “maître prestigieux” – un petit homme étrange, sans nom, qui l’a ébloui par ses océans de connaissances, ses capacités dialectiques hors du commun et ses fulgurances de génie. Alors voici un extrait de ce texte en question, peut-on le déchiffrer et y trouver un hommage à Monsieur Chouchani ? aux lecteurs de juger.

“SANS NOM” (chapitre dans le livre d’Emmanuel Levinas “Noms Propres”)

“(…) il nous faut désormais dans l’inévitable reprise de la civilisation et de l’assimilation, enseigner aux générations nouvelles la force nécessaire pour être fort dans l’isolement de tout ce qu’une fragile conscience est alors appelée à contenir. Il nous faut – en rappelant la mémoire de ceux qui, non-juifs et juifs, surent, sans même se connaitre ni se voir, se comporter en plein chaos comme si le monde n’avait pas été désintégré, en rappelant la Résistance des maquis, c’est-à-dire précisément celle qui n’avait d’autre source que ses propres certitudes et son intimité – il faut, à travers de tels souvenirs, ouvrir vers les textes juifs un accès nouveau et restituer à la vie intérieure un nouveau privilège. La vie intérieure, on a presque honte de prononcer, devant tant de réalismes et d’objectivismes, ce mot dérisoire.

La condition juive

Quand les temples sont debout, quand les drapeaux flottent sur les palais et que les magistrats ceignent leur écharpe – les tempêtes sous les crânes ne menacent d’aucun naufrage. Ce ne sont peut-être que les remous que provoquent, autour des âmes bien ancrées dans leur havre, les brises du monde. La vraie vie intérieure n’est pas une pensée pieuse ou révolutionnaire qui nous vient dans un monde bien assis, mais l’obligation d’abriter toute l’humanité de l’homme dans la cabane ouverte à tous les vents, de la conscience. Et certes, il est fou de rechercher la tempête pour elle-même, comme si “dans la tempête résidait le repos” (Lermontov). Mais que l’humanité installée puisse à tout moment s’exposer à la situation où sa morale tienne tout entière dans un “for intérieur”, où sa dignité reste à la merci des murmures d’une voix subjective et ne se reflète ni ne se confirme plus dans aucun ordre objectif – voilà le risque dont dépend l’honneur de l’homme. Mais c’est peut-être ce risque que signifie le fait même que dans l’humanité se constitue la condition juive. Le judaïsme, c’est l’humanité au bord de la morale sans institutions.

Nous ne disons pas que la condition juive soit aussi une assurance contre ce risque. Peuple comme tous les peuples désireux, lui aussi, de savoir les voix de sa conscience enregistrées dans une civilisation impérissable ; peuple plus vieux, plus sceptique, plus chercheur que les autres, se demandant, avant les autres, si ces voix ne sont pas déjà l’écho d’un ordre historique qui les dépasse. Peuple épris de bonheur, comme tous les autres peuples et amoureux de la douceur de vivre. Mais par une étrange élection, peuple aussi conditionné et ainsi situé parmi les nations – est-ce métaphysique ou est-ce sociologie ? – qu’il s’expose à se retrouver, du jour au lendemain et sans préavis, dans la désolation de son exil, de son désert, de son ghetto ou de son camp, toutes les splendeurs de la vie balayées comme des oripeaux, le Temple en flammes, les prophètes sans vision, réduit à la moralité intérieure – par l’univers démentie. Peuple exposé – même en pleine paix – au propos antisémite, car peuple capable de percevoir dans ce propos un sifflement inaudible à l’oreille commune. Et déjà un vent glacial parcourt les pièces encore décentes ou luxueuses, arrache les tapisseries et les tableaux, éteint les lumières, fissure les murs, met en loques les vêtements et apporte les hurlements et les hululements d’impitoyables foules. Verbe antisémite à nul autre pareil, est-il injure comme les autres injures ?

Verbe exterminateur par lequel le Bien se glorifiant d’Être retourne à l’irréalité et se recroqueville au fond d’une subjectivité, idée transie et tremblante. Verbe révélant à l’Humanité tout entière par l’entremise d’un peuple, élu pour l’entendre, une désolation nihiliste qu’aucun autre discours ne saurait suggérer. Cette élection est certes un malheur.

Mais cette condition où la morale humaine retourne après tant de siècles comme à sa matrice atteste – d’un testament très ancien – son origine d’en deçà les civilisations. Civilisations que cette morale rend possibles, appelle, suscite, salue et bénit, mais qui, elle, ne s’éprouve et ne se justifie que si elle peut tenir dans la fragilité de la conscience, dans les “quatre coudées de la Halacha”, dans cette demeure précaire et divine.”

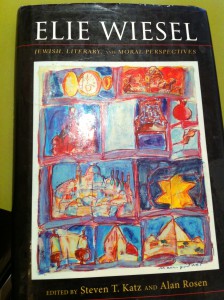

“Shushani and the Problem of Humiliation

Not every teacher thus honored performed their task with equanimity of spirit. Many were angry, some morose. But Mordechai Rosenbaum (aka Harav Mordechai Shushani) presents a special case. His brilliance, erudition, and devotion to study are legendary, as experienced by Wiesel, Emmanuel Levinas, Shalom Rosenberg, and other members of an elite group of students. He was eccentric in appearance, behavior, and method, dressing poorly, maintaining secrecy in his comings and goings, saying little about his past, and holding marathon classes some days and disappearing for long stretches on others. (…) Wiesel also characterizes Harav Shushani as rude and abrupt, stooping so low as to mock, humiliate, and and torment his students. (…)

Harav Shushani did everything, in other words, that his student wouldn’t think of doing. Wiesel’s way is not to humiliate but to humanize.

Indeed, the relationship between Rav Shushani and his admiring student – humiliation on the one hand, loyalty on the other – replays how Wiesel some years later described the relationship between the renegade talmudic master, Elisha ben Abuya, and his lone remaining disciple, Rabbi Meir.(…) Wiesel never refers to Shushani as an apostate (though others apparently did). The question was more the effect of his teaching on the faith of others rather than on his own. Nevertheless, what thy shared was a pedagogy that had room for the humiliation of their closest disciples.

What then did our teacher learn from his own about teaching ? Perhaps he learned what NOT to do; perhaps WE learn, indirectly and paradoxically, that sometimes one chooses a master (or a master chooses a student) from whom one eventually diverges 180 degrees. But then again, it may be that Wiesel’s classroom teaching draws on Shushani’s, while filtering away its excesses.”

from ELIE WIESEL Jewish, Literary and Moral Perspectives. Alan Rosen.

Prof Jacques Goldberg says about his Master Shoshani:

“[That's] how he started teaching me Torah when I was ten, not without quoting that the same method was used over the years, for Bible, Mishna, Talmud … and maths. Because he found me serious and motivated, he just very quickly gave up the requirement of writing, verbal was sufficient.

I would first read the next verse, never more, in Hebrew.

I would then copy the verse, in Hebrew, in my notebook, over two blank pages per verse, and draw columns lines word after word.

In each column I would write down all possible meanings of each individual word without consideration to the neighbor columns.

I would then start a loop in a loop in a loop etc… to build statements meaning by meaning. Most could quickly be discarded as making no sense.

Among those still making sense, I had to select the best, and convince Monsieur Shoshani why I was convinced that this was the best understanding.

And then I only had to convince him that the contrary could as well be correct… before starting the next verse.”

|

Sixty-one years ago, on October 16, 1952, a somewhat peculiar article appeared in the daily Maariv under the heading “Faces on the ship.” The reporter, David Giladi, Yair Lapid’s maternal grandfather, described a group of passengers on their way to Israel from France. “There were many important people onboard the ship, professors and judges, consuls and envoys, but the most popular figure was that Jew named Ben-Chouchan,” he wrote.

This Ben-Chouchan spent his nights on a bench on the upper deck of the ship, bundled up in his coat against the night chill. “The man is unkempt in his outward appearance, dressed in rags, and at first glance you would not give a penny for him,” Giladi wrote. But those who got to know Ben-Chouchan noticed at once that he was no ordinary man. “This is a Torah scholar, the likes of which there are not many, who swims like a champion swimmer in the sea of the Talmud, the midrashim, the earliest and later [biblical] commentators and external sciences,” added Giladi. “His knowledge flows like a fountainhead, and his strange midrashim astound the ears and hearts of his listeners, and his speech is fluent in multiple languages. And if an erudite person is said to be a ‘prodigy,’ then such a one is said to be a ‘genius.’”

Who was that mysterious Jew aboard the ship? What was his full name, where did he come from and where did he go? In the 45 years since his death, in Uruguay, many have wondered about him and tried to crack the riddle of the mysterious figure who was so full of contradictions − a brilliant Jew who knew the Bible, the Talmud and “The Guide for the Perplexed,” by heart, who grasped nuclear physics and solved mathematical mysteries, who lived like a vagabond, beggar and ascetic, but was actually wealthy, and whose money to this day is apparently used to help the indigent, as well as yeshiva students.

His death in Uruguay in 1968 left a great many open questions − but also countless enthusiastic devotees of his teachings, among them intellectuals and scientists, professors and well-known scholars from Israel and elsewhere in the world, who had been his disciples. Among them were Hebrew University professor of Jewish philosophy Shalom Rosenberg and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel and renowned philosopher Emmanuel Levinas.

“People who met him talk about him as if he were the prophet Elijah. Some say he was an angel, others − a devil. But nobody remained indifferent. This strange Jewish genius became a legend,” explained Tel Aviv-based filmmaker Michael Grynszpan last week. Grynszpan has devoted the past few months to exhaustive and cross-continental research into the man he refers to simply as “Mr. Chouchani” (also spelled “Shushani” in some sources), which will be presented in a new, as-yet untitled film. “As far as I’m concerned, he is the puzzle of the 20th century,” he added.

Grynszpan has set up a website and Facebook page to help him make contact with any people who may have known or heard of the subject of his film. Armed with a camera, the filmmaker has been collecting testimonies about his enigmatic persona.

Twelve years after the article appeared in Maariv, in 1964, the mass-circulation Yedioth Ahronoth also reported on the mysterious Jew. Elie Wiesel, who then wrote for the newspaper, published an article in 1964 under the headline “The rabbi − a modern legend,” in which he wrote: “Nobody knew his name, or how old he was. Perhaps he had no name. Perhaps he had no age. He lacked all of those qualities by which a man is defined as belonging to a certain group.”

Adding to the puzzlement surrounding him, “Mr. Chouchan” was apparently in the habit of vanishing and popping up, each time in a new place. Wiesel wrote: “Suddenly he would appear, and then vanish a month or a year later, without leaving a trace. He would accidentally be discovered on the other side of a border … A businessman, a prophet who was dispatched, quite a number of times he went around the world without money, without papers, no one knew how.” Wiesel, too, described the man’s shabby appearance: “He was always filthy, unkempt and dressed in rags. He resembled a vagabond-turned-clown.”

Wiesel had previously met up with Mr. Chouchan on and off for about three years, after the war, after making an initial acquaintance at a small synagogue in Paris. He wrote in the Yedioth article that Chouchan “knew everything, but always lived in the shadows. He read all the books, penetrated all the secrets, traversed all the countries. He was at home everywhere and nowhere. Nobody knew where he lived and what he lived off of … He recognized no law, no authority, neither of time nor of place. He always appeared to have arrived from faraway and magical vacations.”

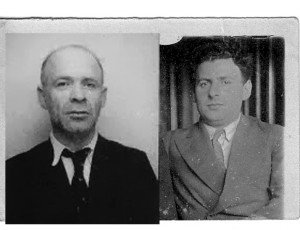

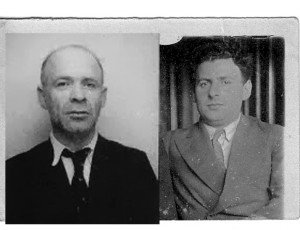

From the articles and testimonies Grynszpan has amassed, and some archival research, the following picture emerges: The wise mysterious Jew in question was born around the beginning of the 20th century, some say in Lithuania and others say in North Africa. His full, real name is unknown. Some say it was “Hillel Perlmann” − a disciple of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook; others believe his name was Mordechai Rosenbaum; many refer to him as “Mr. Chouchan,” or simply “Chouchani.”

He apparently survived the Holocaust thanks to his sharpness and courage. There is one story about him being arrested by the Germans and taken for interrogation by the Gestapo. In his interrogation he claimed to be Aryan, a native of the Alsace region, a professor of mathematics at the University of Strasbourg. The interrogating officer, sneering at the sight of the beggar with airs of being a professor, said to Chouchan, according to the stories: “You have made a grave mistake. In civilian life I myself was a professor of mathematics.”

Chouchan, so the story goes, suggested making a deal with the devil, with the Nazi officer: He would present the officer with a tough mathematical riddle, and if the officer solved it − he would execute Chouchan. If he failed, he would have to let the man go free. A short while later, Chouchan was released, and he escaped to Switzerland after making a difficult journey.

According to another story, he was arrested by the Nazis in Paris and forced to undress. When they saw he was circumcised, he told them he was a Muslim. Then he amazed all present by reciting parts of the Koran perfectly − to the point where an imam who was brought in by the Germans confirmed that the detainee was indeed Muslim.

After the Holocaust, according to the research, he began to wander the globe, acquiring numerous students and admirers on various continents. He died 45 years ago, and his gravestone in Montevideo reads: “The wise Rabbi Chouchani of blessed memory. His birth and his life are sealed in enigma.”

Hebrew University’s Rosenberg was asked recently in an interview with the history magazine Segula which spiritual figure from the past most impressed him. The answer was unequivocal: “Mr. Chouchani, who is also called Prof. Chouchani.” Rosenberg said that Chouchani’s name had been tied to “a lot of legends, none of which I believed [at first], and after meeting him I said that any person who tells me that what has been said about him is not possible or that it’s a myth − that person does not understand his greatness.”

Meanwhile, Grynszpan is continuing to search for people with information about Chouchani. “I am midway through [my research] but maybe actually only at the beginning,” says the filmmaker, who has been collecting testimonies in Israel, Canada, the U.S. and France, where he met a 100-year-old woman who studied with the enigmatic scholar. Soon Grynszpan will travel to the final stop in Mr. Chouchan’s life: Uruguay.

“They say he was crazy, insane and inhuman. They say he had a phenomenal photographic memory, for anything. There are so many wild stories about this human being,” he summed up.

Levinas said: “Shoshani? there is no other subject”. (in the book of S. Malka in French “Monsieur Chouchani: L’énigme d’un maitre du XXe siècle”)

Levinas a dit: “Chouchani ? il n’y a pas d’autre sujet”. (source : dans le livre de S. Malka “Monsieur Chouchani : L’énigme d’un maitre du XXe siècle”)

פרופ’ לוינס אמר : “שושני ? אין נושא (סובייקט) אחר (מקור: מתוך הספר מאת שלמה מלכה “מר שושני”, שעדיין לא תורגם לעברית