מר שלמה מאיר מדבר על מר שושני: “זה תופעה פתאומית מהשמיים שהתישב בינינו, וסוף סוף נעלם”. תשמעו

מר שלמה מאיר מדבר על מר שושני: “זה תופעה פתאומית מהשמיים שהתישב בינינו, וסוף סוף נעלם”. תשמעו

On Shoshani’s grave, in Uruguay, no real name. Only this sentence: “The wise Rabbi Shoshani of blessed memory.

His birth and his life are sealed in enigma.”

Sur la tombe de Chouchani en Uruguay, il n’y a pas son vrai nom. Seulement cette phrase :

“Le rabbin et le sage Chouchani, que sa mémoire soit bénie,

Sa naissance et sa vie sont scellées dans l’énigme”.

על קברו של שושני באורוגואיי, אין שמו האמיתי. רק משפט הזה : “הרב והחכם שושני ז”ל

לידתו וחיו סתומים בחידה”

Albert Einstein: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.  He to whom the emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand wrapped in awe, is as good as dead —his eyes are closed. The insight into the mystery of life, coupled though it be with fear, has also given rise to religion. To know what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty, which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling is at the center of true religiousness.”

He to whom the emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand wrapped in awe, is as good as dead —his eyes are closed. The insight into the mystery of life, coupled though it be with fear, has also given rise to religion. To know what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty, which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling is at the center of true religiousness.”

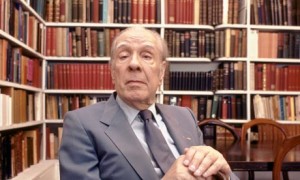

According to many witnesses in Uruguay, Jorge Luis Borges was secretly learning with Professor Shoshani in Montevideo.

According to many witnesses in Uruguay, Jorge Luis Borges was secretly learning with Professor Shoshani in Montevideo.

Here is a short story about that:

http://www.raoulwallenberg.net/wp-content/files_mf/6680.pdf

Levinas says in an interview:

“I am extremely grateful for what I learned from him [Shoshani]. In a haggadic text of the treatise  Pirke Avoth, there is this phrase: “The words of the sages are like glowing embers.” One can ask, why embers, why not flame? Because it only becomes a flame when one knows how to blow on it! I have hardly learned to blow. There are always great minds who contest this manner of blowing. They say, “You see, he draws out of the text what is not in the text. He forces a meaning into it.” But if one does it with Goethe, with Valery, with Corneille, the critics accept it. It appears more scandalous to them when one does it with regard to Scripture. And one has to have met Shoshani in order not to be convinced by these critical minds. Shoshani taught me: what is essential is that the meaning found merits, by its wisdom, the research that reveals it. That the text had suggested it to you.”

Pirke Avoth, there is this phrase: “The words of the sages are like glowing embers.” One can ask, why embers, why not flame? Because it only becomes a flame when one knows how to blow on it! I have hardly learned to blow. There are always great minds who contest this manner of blowing. They say, “You see, he draws out of the text what is not in the text. He forces a meaning into it.” But if one does it with Goethe, with Valery, with Corneille, the critics accept it. It appears more scandalous to them when one does it with regard to Scripture. And one has to have met Shoshani in order not to be convinced by these critical minds. Shoshani taught me: what is essential is that the meaning found merits, by its wisdom, the research that reveals it. That the text had suggested it to you.”

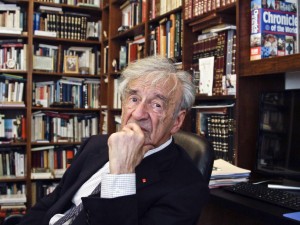

In an interview of Elie Wiesel in 1978:

In an interview of Elie Wiesel in 1978:

INTERVIEWER

What about Rav Mordechai Shushani? Where did you and he meet?

WIESEL

We met in Paris and I stayed with him for several years. He was a strange man. A genius who looked like a bum, or a clown. He pushed me to the abyss. But he believed in that. One day I am going to write a monograph about him. His concept was to shock, to shake you up, to push you further and further. If you don’t succeed, too bad. But you must risk it. If I had stayed with him longer, I don’t know what would have happened.

INTERVIEWER

Did he push anybody over the abyss?

WIESEL

He did. I heard stories later when I began picking up pieces looking for him. He did it with the best of intentions. Few people have had such an influence on my life as he did.

INTERVIEWER

Who were the others?

WIESEL

Here and there a teacher, a friend. But he is probably the strongest. He’s the opposite of Professor Saul Lieberman, who is no longer alive, but whom I considered to be the greatest Jewish scholar of his day. One cannot study the Talmud without the help of his commentaries. He was my friend and my teacher. Shushani, on the other hand, was not my friend. Surely he possessed a certain strength and power; so did Professor Lieberman—but his was not frightening.

From Mister Shoshani Elie Wiesel learned that “Man is defined by what troubles him, not by what reassures him.”

Elie Wiesel a appris de Monsieur Chouchani que “l’homme se définie par ce qui l’inquiète, non pas par ce qui le rassure”.

אלי ויזל למד ממר שושני ש”האדם מוגדר על-ידי מה שמדאיג אותו, ולא על-ידי מה

שמרגיע אותו

Monsieur Chouchani (? – 1968), or “Shushani,” is the nickname of an otherwise anonymous and enigmatic Jewish teacher who taught a small number of distinguished students in post-World War II Europe and elsewhere, including Emmanuel Levinas and Elie Wiesel.

Not much is known about “M. Chouchani,” including his real name, a secret which he zealously guarded. His origins are completely unknown, and his gravestone (located in Montevideo, Uruguay, where he died in January 1968) reads, “The wise Rabbi Chouchani of blessed memory. His birth and his life are sealed in enigma.” The text is by Elie Wiesel who paid for this gravestone. The name “Shushani,” which means “person from Shushan,” is most probably an allegorical reference, or possibly a pun. Elie Wiesel hypothesizes that Chouchani’s real name was Mordechai Rosenbaum, while Hebrew University professor Shalom Rosenberg asserts that Chouchani’s actual name was Hillel Perlmann.

Although there is no known body of works by Chouchani himself, there is a very strong intellectual legacy seen in the influence on his pupils. By all accounts, Chouchani had the appearance of a vagabond and yet was reputed to be a master of vast areas of human knowledge, including science, mathematics, philosophy and especially the Talmud. Most of the biographical details of Chouchani’s life are known from the works and interviews of his various students, as well as anecdotes of people whom he encountered during his lifetime.

Chouchani appeared in Paris after the Second World War, where he taught between the years of 1947 and 1952. He disappeared for a while after that, evidently spent some time in the newly-formed state of Israel, returned to Paris briefly, and then left for South America where he lived until his death.

עמנואל לוינס אומר על מורו ורבו שושני

Elie Wiesel écrit sur son Maitre : “Mystère sept fois vérrouillé. Il ne parlait de lui-même que pour dérouter : oui et non se valaient, le bien et le mal tiraient dans la même direction. Ses théories, il les construisait et les démolissait du même coup, en faisant usage des mêmes moyens. Plus on l’écoutait et moins on en apprenait sur sa vie, sur le monde qui l’habitait. Il possédait le pouvoir surhumain de se refaire un passé. Il inspirait la peur. L’admiration aussi, bien sûr. On disait de lui : “C’est un personnage dangereux, il sait trop de choses.” Il aimait qu’on le dît. Il se voulait seul, étranger, inaccessible.”

les construisait et les démolissait du même coup, en faisant usage des mêmes moyens. Plus on l’écoutait et moins on en apprenait sur sa vie, sur le monde qui l’habitait. Il possédait le pouvoir surhumain de se refaire un passé. Il inspirait la peur. L’admiration aussi, bien sûr. On disait de lui : “C’est un personnage dangereux, il sait trop de choses.” Il aimait qu’on le dît. Il se voulait seul, étranger, inaccessible.”