Chouchani: a Genius, a Bum, a Legend

If you are curious and eager to know more, you may be interested in a lecture about M. Chouchani in English, Hebrew or French. Feel free to contact us: contactfilm@chouchani.com

We have already been invited many times to give lectures and tell the story of this amazing unique character.

We then show exclusive video interviews and reveal concealed parts of the documentary movie we are working on.

Tag Archives: genius

Chouchani is One of the Ten Most Mysterious Men Ever

New book in Italian with Monsieur Chouchani’s spirit

New book in Italian by Haim Baharier with Monsieur Chouchani’s spirit:

Elie Wiesel-Chouchani’s relationship and influence.

Interesting article on Elie Wiesel-Chouchani’s relationship and influence.

“Shushani’s influence on Wiesel cannot be overstated. “It is to him I owe my constant drive to question, my pursuit of the mystery that lies within knowledge and of the darkness hidden within light.” “(…)

“What, then, was the turning point in Wiesel’s life that led to his writing of Night?–and to a remarkable career of bearing witness to the Holocaust and to speaking out on behalf of all who suffer from oppression and injustice? Arguably, it was his unsettling initial experience with the wise teacher Shushani.

From Shushani he learned about Job, Midrash, the Talmud, and humanity. From Shushani he learned to question certainties, to care deeply about the suffering of others, and to acknowledge the power (and limitation) of words. Eventually, and above all, these lessons led Wiesel to a sense of responsibility, of personal moral accountability in the face of oppression and suffering.

From Shushani Wiesel learned that “Man is defined by what troubles him, not by what reassures him.” He learned that despite the limitation of words, he had to make his deposition.”

http://www.freepatentsonline.com/article/Cross-Currents/174012201.html

His method of teaching a young boy who later became Professor

Prof Jacques Goldberg says about his Master Shoshani:

“[That's] how he started teaching me Torah when I was ten, not without quoting that the same method was used over the years, for Bible, Mishna, Talmud … and maths. Because he found me serious and motivated, he just very quickly gave up the requirement of writing, verbal was sufficient.

I would first read the next verse, never more, in Hebrew.

I would then copy the verse, in Hebrew, in my notebook, over two blank pages per verse, and draw columns lines word after word.

In each column I would write down all possible meanings of each individual word without consideration to the neighbor columns.

I would then start a loop in a loop in a loop etc… to build statements meaning by meaning. Most could quickly be discarded as making no sense.

Among those still making sense, I had to select the best, and convince Monsieur Shoshani why I was convinced that this was the best understanding.

And then I only had to convince him that the contrary could as well be correct… before starting the next verse.”

How to understand the Talmud – according to Monsieur Chouchani

How to understand the Talmud – according to Monsieur Chouchani

“The fundamental principle is reported by Levinas in the name of his teacher, Chouchani: “One does not have to construct nor speculate abstractly, but through imagination.” On this are based the following assumptions:

1. Reading Talmud requires sensitivity to images, ideas, reactions, random thoughts, even distractions, that occur in the process of reading.

2. Reading Talmud requires asking questions, permitted or not.

3. The Talmud should be read aloud to approximate an oral tradition.

4. The Talmud is to be taken as a whole.

5. The Talmud is part of the story of the encounter between Israel and the “Nameless Being.” This encounter precludes a sensibility of oppression.

6. Although historical and scientific information is essential for a proper reading of the Talmud, such information must be subject to the same images, ideas, reactions, random thoughts, even distractions and – especially – questions as the text.

7. The mention of “Israel” means human being. As Levinas wrote:

Each time Israel is mentioned in the Talmud one is free, certainly, to understand by it a particular ethnic group which is probably fulfilling an incomparable destiny. But to interpret in this manner would be to reduce the general principle in the idea enunciated in the Talmudic passage, would be to forget that Israel means a people who has received the Law and, as a result, a human nature which has reached the fullness of its responsibilities and of its self-consciousness… the heirs of Abraham are all nations; any man truly man is no doubt of the line of Abraham.”

In “Reading Levinas/Reading Talmud: An Introduction”

By Ira F. Stone

Maestro Shoshani – video

In Spanish. En Espagnol

En español

בספרדית:

“Sur les traces de Chouchani” article de Sandra Ores pour la MENA

Un très bon article de Sandra Ores pour la MENA sur notre film sur Monsieur Chouchani.

Un très bon article de Sandra Ores pour la MENA sur notre film sur Monsieur Chouchani.

Sur les traces de Chouchani (info # 012112/13) [Culture]

Par Sandra Ores © Metula News Agency (www.menapress.org)

Jacob lutta jusqu’à l’aube avec l’homme. Celui-ci, voyant qu’il ne pouvait le vaincre, le blessa à la hanche. L’homme demanda à Jacob son nom, puis le renomma Israël. Jacob lui retourna la question à son tour, mais l’homme répondit “pourquoi demandes-tu mon nom ?”, et ne lui donna point de réponse.

Comme l’homme avec lequel s’est battu Jacob dans le récit biblique, le personnage énigmatique de Chouchani, érudit du XXème siècle, qui fut le maître inégalé de grands penseurs de notre temps, ne révéla jamais son identité.

L’homme qui apparut puis disparut auprès de Jacob fut rebaptisé “l’ange” par les commentateurs rabbiniques décelant dans sa manifestation une présence transcendantale ; de la même manière, les disciples de Chouchani ont perçu dans ce génie du Talmud, de la philosophie, des mathématiques, et maître dans bien d’autres domaines encore, une dimension surnaturelle.

Chouchani n’était d’ailleurs pas son véritable nom. Ce pseudonyme découle du mot hébreu chouchan, qui signifie fleur de lys ; la fleur, pressée sur la face de la pièce d’un shekel, représente un symbole ancien d’Israël.

Caméra à l’épaule, le réalisateur franco-israélien Michael Grynszpan s’atèle à reconstituer le puzzle Chouchani, lequel avait le plus souvent l’allure d’un clochard. Mais Emmanuel Levinas, Elie Wiesel, Jacques Abramoff et d’autres éminents professeurs ont couvert d’éloges les plus respectueuses son intelligence et son savoir.

“Ce maître prestigieux et impitoyable en exégèse et en Talmud” (le Talmud, la Torah orale), tel que le décrivait Levinas, qui a certainement beaucoup appris de lui en matière d’éthique – l’un des principaux domaines d’intérêt et de recherche du philosophe français.

S’il récitait le Talmud, le Zohar1 ou le Guide des Egarés2 de Maïmonide par cœur, Chouchani en faisait de même avec le Coran ou les Vedas3. Il possédait une mémoire ainsi qu’un esprit de synthèse exceptionnels. “Il savait tout”, commenta Wiesel dans un article du quotidien israélien Yediot Aharonot en 1964 ; Wiesel, qui fut son élève pendant trois ans à Paris, et qui considère Chouchani comme l’un de ses plus influents professeurs, écrivit également à son sujet qu’ “il avait lu tous les livres, pénétré tous les secrets, traversé tous les pays”.

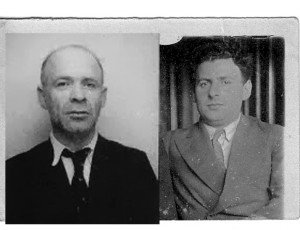

chouchani.jpg

L’une des rares photographies de Chouchani

Depuis presqu’une année qu’il planche sur son sujet, Michaël Grynszpan, totalement absorbé, parle sans arrêt de Chouchani. Ce n’est pas la première fois que le réalisateur se penche sur un thème au demeurant abstrus ; en 2011, son film “Descendants de nazis : l’héritage infernal”, montrait des descendants de nazis vivant en Israël, certains s’étant convertis au judaïsme ; son documentaire “Les oubliés de l’histoire” (2005), consacre quant à lui la mémoire des Juifs originaires du Moyen-Orient, réfugiés en Israël suite aux violences dont ils furent victimes lors des mouvements nationalistes arabes du milieu du XXème siècle.

Grynszpan se passionne désormais pour ce héros encore flou dont il approche pas à pas le mystère ; à force de recherches et de rencontres avec ceux qui ont croisé le chemin de Chouchani, il recoupe les bribes d’informations dans le but de toucher du doigt la clé de voute de la logique et de la magie du personnage. Sentir la réalité de ce passeur de sciences nomade s’apparente pourtant à tenter de regarder à travers une vitre opaque.

Car en dépit de sa grandeur et de l’influence qu’il a eue sur des hommes ayant plus tard réalisé une brillante carrière, Chouchani est resté dans l’ombre. C’est que, pour lui, maintenir le secret sur sa propre vie relevait de l’obsession.

A en croire Elie Wiesel, Chouchani parlait une trentaine de langues anciennes et modernes ; mais nul ne connaissait son origine. “Son français était pur, son anglais parfait et son yiddish se pliait aux accents de son interlocuteur”, écrivit Elie Wiesel. Des récits concourent cependant à établir qu’il aurait survécu à la Shoah.

Personne ne lui connaissait non plus ni âge, ni adresse, ni métier, ni famille, ni amour ; “il lui manquait toutes ces caractéristiques qui définissent habituellement un homme en tant qu’élément d’un groupe”, renchérit le Prix Nobel de la paix 1986, qui explique en outre que, sans laisser de trace, il apparaissait et disparaissait à divers endroits du globe, qu’il était chez lui partout et nulle part.

Chouchani n’a laissé aucun écrit ; il a transmis toute sa science par oral à ceux qui ont eu la chance de recevoir ses enseignements – ou la folie de se laisser prendre au jeu de son intelligence aux limites impalpables.

Mais si quarante-cinq ans après la mort de cet homme mystérieux, peu de ceux qui l’ont rencontré ont effectivement dévoilé des indices, c’est aussi parce que, parmi ces hommes et ces femmes, certains craignent d’en parler ; car révéler ses secrets équivaut, en quelque sorte, à transgresser son vœu d’anonymat. Des témoins, dont des individus des plus sérieux et pragmatiques, ont refusé de se confier au réalisateur, craignant probablement que la mémoire de l’homme ne vienne les hanter. Rien d’étonnant à ce que Grynszpan se réveille parfois la nuit, imaginant Chouchani incriminant son travail.

Le professeur d’histoire émérite de l’université israélienne Bar-Ilan, Tsvi Bachrach, subjugué par sa rencontre avec le vagabond prodige, au début des années 50 dans le jeune Etat hébreu, refusa tout d’abord de rencontrer le réalisateur, prétextant “qu’il y avait quelque chose d’effrayant dans cette histoire”.

Shalom Rosenberg, éminent intellectuel israélien, professeur de philosophie juive à l’Université Hébraïque de Jérusalem, suivit lui aussi les enseignements de Chouchani. Lors de l’entretien qu’il concéda à Michael Grynszpan, l’enregistrement du son se brouilla soudain ; “c’est du pur Chouchani !”, marmonna-t-il en souriant. Rosenberg confia au cinéaste que, s’il avait eu un jour Chouchani en face de lui, il aurait alors compris la raison de sa plaisanterie.

Grâce à l’image, Grynszpan parvient à capter les regards mêlés d’effroi, d’envoûtement et d’admiration de ses interlocuteurs, ces éclairs qui dépeignent avec le plus d’authenticité le souffle de Chouchani. “Ce n’était pas humain”, confia Zvi Bachrach. L’un des maîtres à penser des Juifs de France après la guerre, le rabbin Léon Ashkénazi, autrement connu sous le totem de Manitou, se demandait quant à lui “s’il était un homme ou autre chose”.

Afin de rassembler les témoignages, d’Europe, des Amériques, d’Afrique du Nord, d’Asie et des divers pays du monde dont Chouchani a foulé le sol, Michael Grynszpan a créé un site Internet appelant ceux qui ont croisé sa route à s’exprimer. Il reste encore six mois d’enquête et c’est en Uruguay, notamment à Montevideo, où le génie fou s’est éteint, que l’équipe de tournage se rendra prochainement.

Mais plus que d’entendre des opinions au sujet du personnage invraisemblable, ce que cherche avant tout Grynszpan, c’est saisir l’essence et l’architecture de sa pensée, percer la source de ses enseignements, dévoiler les motivations enceintes dans ses pérégrinations. Avait-il compris le sens des innombrables choses de ce monde qui nous échappent ? Etait-il parvenu à entendre le Om sacré (la syllabe sanskrite figurant la perfection, l’unité du monde) ?

Wiesel écrivit, dans son livre Le Chant des morts (ed. du Seuil, 1966), que son mentor “aimait déplacer les points fixes”. L’une de ses particularités consistait à faire jouer les correspondances à partir des éléments d’un texte avec des repères situés dans des domaines complètement distincts ; il plaçait les problématiques dans des contextes infiniment plus larges et inattendus, s’inspirant notamment du Talmud, qu’il percevait comme une source inépuisable et originale de philosophie et d’éthique. Le penseur remettait tout en question, construisait et démolissait ses théories du même coup. Etre son élève devait être épuisant.

Chouchani fut assurément un personnage contradictoire sous tous ses aspects. Il vécut dans la plus grande simplicité, voire en dessous des limites de la décence, hirsute, mangeant salement, dormant sur des bancs, toujours coiffé du même chapeau, mais n’était pas pauvre pour autant ; il aurait gagné beaucoup d’argent en jouant à l’homme d’affaires. Encore aujourd’hui, sa fortune profite à des familles pauvres d’Israël.

Claude Riveline, ingénieur polytechnicien, professeur à l’Ecole des Mines à Paris, auteur de nombreux écrits sur la gestion des organisations et l’influence des “tribus, des rites et des mythes”, rencontra Chouchani pendant moins d’une heure en 1962. Il raconte avoir eu une sensation qui lui était jusque-là inconnue ; celle de se laisser pénétrer complètement par les mots de son interlocuteur, d’en comprendre aussitôt tout le sens. Riveline compare cette situation à la révélation de la Torah sur le mont Sinaï, lorsque, selon le récit, les 600 000 âmes présentes auraient entendu la parole du Dieu d’Israël.

L’ingénieur instille ainsi que Chouchani était doté de la capacité exceptionnelle de connaître et de saisir l’âme des hommes ; de s’y adresser et de s’en faire comprendre parfaitement, en nuançant son discours selon l’âge, le niveau de connaissance, les capacités émotionnelles et intellectuelles de celui ou celle qu’il avait en face de lui. Chouchani avait aussi la vocation de transmettre sa science aux esprits avides de savoir. Dans pas longtemps, Michael Grynszpan sera certainement capable de nous en apprendre un peu plus sur ce personnage mythique et sur sa dialectique.

Notes :

1Zohar : l’un des ouvrages principaux de la Kabale, exégèse ésotérique de la Torah.

2Le Guide des Egarés de Moïse Maïmonide est l’œuvre majeure de ce philosophe juif, considéré comme le plus marquant du Moyen-Age, qui était également rabbin et médecin dans l’Andalousie musulmane du XIIème siècle. Cet ouvrage, dans le quel l’auteur examine entre autres la relation entre la philosophie et la religion, a influencé les philosophes juifs et non juifs des siècles suivants.

3Vedas, ou connaissances en sanskrit : ensemble de textes qui auraient été révélés aux sages indiens, et transmis oralement de brahmane à brahmane jusqu’à nos jours. Un brahmane, dans les sociétés hindouistes, est un membre de l’une des quatre castes regroupant les hommes de lettres et les érudits, et notamment les sacrificateurs et les prêtres.

Metula News

Agency ©

“Magical Mystery Man” – new article in Haaretz about Mr. Shoshani

A beautiful mind: The mysterious Jewish genius whose riddle saved him

Filmmaker Michael Grynszpan is trying to unravel the enigma named Chouchan, an indigent wanderer and scholar of Torah and other subjects, whose full name and biography are still unknown 45 years after his death.

|

Sixty-one years ago, on October 16, 1952, a somewhat peculiar article appeared in the daily Maariv under the heading “Faces on the ship.” The reporter, David Giladi, Yair Lapid’s maternal grandfather, described a group of passengers on their way to Israel from France. “There were many important people onboard the ship, professors and judges, consuls and envoys, but the most popular figure was that Jew named Ben-Chouchan,” he wrote.

This Ben-Chouchan spent his nights on a bench on the upper deck of the ship, bundled up in his coat against the night chill. “The man is unkempt in his outward appearance, dressed in rags, and at first glance you would not give a penny for him,” Giladi wrote. But those who got to know Ben-Chouchan noticed at once that he was no ordinary man. “This is a Torah scholar, the likes of which there are not many, who swims like a champion swimmer in the sea of the Talmud, the midrashim, the earliest and later [biblical] commentators and external sciences,” added Giladi. “His knowledge flows like a fountainhead, and his strange midrashim astound the ears and hearts of his listeners, and his speech is fluent in multiple languages. And if an erudite person is said to be a ‘prodigy,’ then such a one is said to be a ‘genius.’”

Who was that mysterious Jew aboard the ship? What was his full name, where did he come from and where did he go? In the 45 years since his death, in Uruguay, many have wondered about him and tried to crack the riddle of the mysterious figure who was so full of contradictions − a brilliant Jew who knew the Bible, the Talmud and “The Guide for the Perplexed,” by heart, who grasped nuclear physics and solved mathematical mysteries, who lived like a vagabond, beggar and ascetic, but was actually wealthy, and whose money to this day is apparently used to help the indigent, as well as yeshiva students.

His death in Uruguay in 1968 left a great many open questions − but also countless enthusiastic devotees of his teachings, among them intellectuals and scientists, professors and well-known scholars from Israel and elsewhere in the world, who had been his disciples. Among them were Hebrew University professor of Jewish philosophy Shalom Rosenberg and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel and renowned philosopher Emmanuel Levinas.

“People who met him talk about him as if he were the prophet Elijah. Some say he was an angel, others − a devil. But nobody remained indifferent. This strange Jewish genius became a legend,” explained Tel Aviv-based filmmaker Michael Grynszpan last week. Grynszpan has devoted the past few months to exhaustive and cross-continental research into the man he refers to simply as “Mr. Chouchani” (also spelled “Shushani” in some sources), which will be presented in a new, as-yet untitled film. “As far as I’m concerned, he is the puzzle of the 20th century,” he added.

Grynszpan has set up a website and Facebook page to help him make contact with any people who may have known or heard of the subject of his film. Armed with a camera, the filmmaker has been collecting testimonies about his enigmatic persona.

Twelve years after the article appeared in Maariv, in 1964, the mass-circulation Yedioth Ahronoth also reported on the mysterious Jew. Elie Wiesel, who then wrote for the newspaper, published an article in 1964 under the headline “The rabbi − a modern legend,” in which he wrote: “Nobody knew his name, or how old he was. Perhaps he had no name. Perhaps he had no age. He lacked all of those qualities by which a man is defined as belonging to a certain group.”

Adding to the puzzlement surrounding him, “Mr. Chouchan” was apparently in the habit of vanishing and popping up, each time in a new place. Wiesel wrote: “Suddenly he would appear, and then vanish a month or a year later, without leaving a trace. He would accidentally be discovered on the other side of a border … A businessman, a prophet who was dispatched, quite a number of times he went around the world without money, without papers, no one knew how.” Wiesel, too, described the man’s shabby appearance: “He was always filthy, unkempt and dressed in rags. He resembled a vagabond-turned-clown.”

Wiesel had previously met up with Mr. Chouchan on and off for about three years, after the war, after making an initial acquaintance at a small synagogue in Paris. He wrote in the Yedioth article that Chouchan “knew everything, but always lived in the shadows. He read all the books, penetrated all the secrets, traversed all the countries. He was at home everywhere and nowhere. Nobody knew where he lived and what he lived off of … He recognized no law, no authority, neither of time nor of place. He always appeared to have arrived from faraway and magical vacations.”

From the articles and testimonies Grynszpan has amassed, and some archival research, the following picture emerges: The wise mysterious Jew in question was born around the beginning of the 20th century, some say in Lithuania and others say in North Africa. His full, real name is unknown. Some say it was “Hillel Perlmann” − a disciple of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook; others believe his name was Mordechai Rosenbaum; many refer to him as “Mr. Chouchan,” or simply “Chouchani.”

He apparently survived the Holocaust thanks to his sharpness and courage. There is one story about him being arrested by the Germans and taken for interrogation by the Gestapo. In his interrogation he claimed to be Aryan, a native of the Alsace region, a professor of mathematics at the University of Strasbourg. The interrogating officer, sneering at the sight of the beggar with airs of being a professor, said to Chouchan, according to the stories: “You have made a grave mistake. In civilian life I myself was a professor of mathematics.”

Chouchan, so the story goes, suggested making a deal with the devil, with the Nazi officer: He would present the officer with a tough mathematical riddle, and if the officer solved it − he would execute Chouchan. If he failed, he would have to let the man go free. A short while later, Chouchan was released, and he escaped to Switzerland after making a difficult journey.

According to another story, he was arrested by the Nazis in Paris and forced to undress. When they saw he was circumcised, he told them he was a Muslim. Then he amazed all present by reciting parts of the Koran perfectly − to the point where an imam who was brought in by the Germans confirmed that the detainee was indeed Muslim.

After the Holocaust, according to the research, he began to wander the globe, acquiring numerous students and admirers on various continents. He died 45 years ago, and his gravestone in Montevideo reads: “The wise Rabbi Chouchani of blessed memory. His birth and his life are sealed in enigma.”

Hebrew University’s Rosenberg was asked recently in an interview with the history magazine Segula which spiritual figure from the past most impressed him. The answer was unequivocal: “Mr. Chouchani, who is also called Prof. Chouchani.” Rosenberg said that Chouchani’s name had been tied to “a lot of legends, none of which I believed [at first], and after meeting him I said that any person who tells me that what has been said about him is not possible or that it’s a myth − that person does not understand his greatness.”

Meanwhile, Grynszpan is continuing to search for people with information about Chouchani. “I am midway through [my research] but maybe actually only at the beginning,” says the filmmaker, who has been collecting testimonies in Israel, Canada, the U.S. and France, where he met a 100-year-old woman who studied with the enigmatic scholar. Soon Grynszpan will travel to the final stop in Mr. Chouchan’s life: Uruguay.

“They say he was crazy, insane and inhuman. They say he had a phenomenal photographic memory, for anything. There are so many wild stories about this human being,” he summed up.

Levinas said: “Shoshani? there is no other subject”

Levinas said: “Shoshani? there is no other subject”. (in the book of S. Malka in French “Monsieur Chouchani: L’énigme d’un maitre du XXe siècle”)

Levinas a dit: “Chouchani ? il n’y a pas d’autre sujet”. (source : dans le livre de S. Malka “Monsieur Chouchani : L’énigme d’un maitre du XXe siècle”)

פרופ’ לוינס אמר : “שושני ? אין נושא (סובייקט) אחר (מקור: מתוך הספר מאת שלמה מלכה “מר שושני”, שעדיין לא תורגם לעברית